According to NCD (non communicable disease) Risk Factor Collaboration (2019), rural areas now contribute 55% to the world’s rise in mean body mass index (BMI), a statistic previously dominated by the urban population.

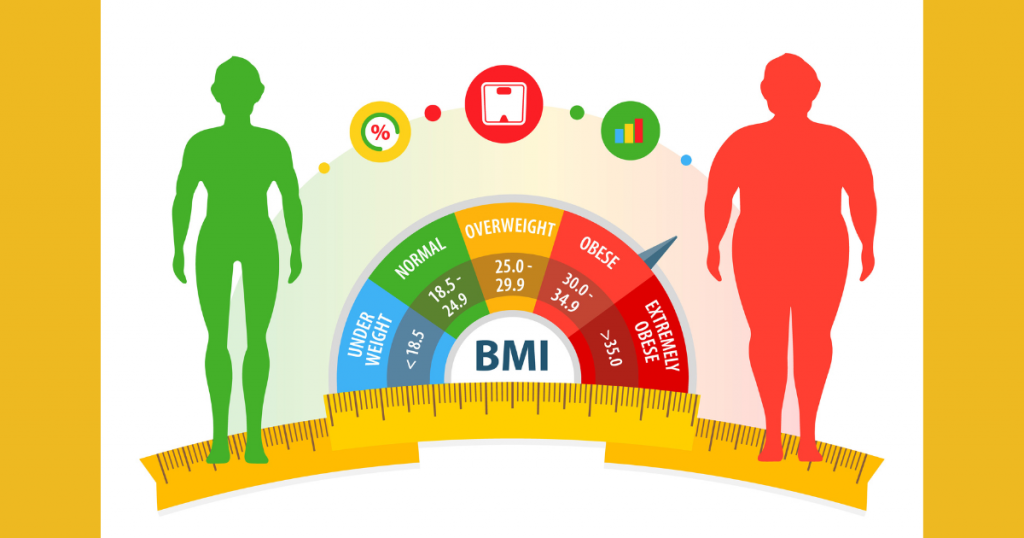

The near tripling of worldwide obesity since 1975, as reported by the World Health Organisation, is an indication of our failure to identify and curb a complex condition with health implications spanning from psychological complications to chronic health disorders. The early to mid-twentieth century witnessed obesity in the groups dominating the socioeconomic ladder, with malnutrition wreaking havoc on the other side of the spectrum. According to NCD (none communicable disease) Risk Factor Collaboration (2019), rural areas now contribute 55% to the world’s rise in mean body mass index (BMI), a statistic previously dominated by the urban population.

The new age of obesity has expanded its range and has mutated to coexist with undernutrition, giving way to a paradoxical amalgamation of the worst of the two worlds. Regular consumption of calorie-dense and nutrient-scarce meals temporarily relieves the brain of its hunger but also leaves a void, essential for various bodily processes, warranting deficiencies and creating favourable conditions for chronic diseases to flourish. Data from worldobesity.org predicted the burden on India’s economy by 2060 to cross the 400 billion mark.

Considering obesity’s alliance with life-threatening conditions and the resulting financial stress in today’s world, it has renounced its societal status from being a personal struggle in the past to a global threat today. Addressing obesity requires pulling the plugs on the supporting factors that have caused this evil seed to flourish and pollute the faculties responsible for a healthy life.

The subscribers to these bloggers reported feeling empowered and improved mental well-being as a consequence of belonging to a supportive community.

Visual Normalization Theory (VNT)

Research has consistently shown that when confronted with questions about one’s perceived weight, relatively healthier people provide realistic numbers, and people who weigh more, or are on the brink of obesity, underestimate considerably. A nationwide survey conducted in the UK, in 2013, reported that 55% of men and 31% of women denied being overweight even though they were. Eric Robinson, from Liverpool University, proposed this theory to dissect the widely accepted proposition that underestimation of weight can further complicate a person’s comeback from their actual weight. The incorrect estimate of one’s weight is either an honest admission or a deliberate attempt to sustain the preexisting state of denial, evading being categorised as part of a stigmatised social group.

As Eric Robinson wrote in his paper (Overweight but unseen: a review of the underestimation of weight status and a visual normalization theory), “Perception is shaped by previous experience, and because of this, increased obesity prevalence is likely to have recalibrated visual body‐weight norms”. Gradual tuning of one’s perception influenced by visual familiarity with heavier bodies has impaired the ability to identify and separate healthy from unhealthy, widening the inclusivity of the previously rigid health norms. Flexible norms have psychological merits as it lends the comfort of being a part of the ‘healthy group’, a luxury otherwise bestowed to the people occupying the lower end of the BMI scale. Robert E. Roberts and Hao T. Duong found a strong independent association between perceived weight and major depression in adolescents, suggesting an etiologic link between obesity and depression, with weight perception bridging the gap.

Perception untouched by awareness begets confusion, not leaving much space for potentially helpful interventions. Weight issues, be it anorexia or an alarming fat-reserve growth, emerge from calorie imbalance. Failure to acknowledge this gives way to fear-infused individualised definitions for an already well-researched phenomenon that doesn’t require more versions.

Hunter-Gatherers

Hunter-gatherers only have access to food when they deliberately decide to move and aren’t privileged to get food delivered to them by a fellow homo sapien. They largely survive on nutrient-rich, low-calorie diets and have excellent cardiovascular and metabolic health, not to forget, that obesity prevalence in this community, as reported by H Pontzer and team, is below 5%. Physical activity and low-calorie diets are the reasons behind this community’s exceptional health, and one doesn’t need a specialised degree to acknowledge that. The spread of such information should be our motive in eradicating doubts from the minds struggling with their weight. This, however, comes with another set of problems that deserve a separate section.

Insecurities and Body Positivity

Body positivity is the new age’s tool that gets wielded by people every time their insecurities are cornered. Under this movement, terms like fat, obese, and overweight are derogatory slurs directed at big-bodied people. In short, should not be used in the public domain. This movement previously concerned those subjected to fat-shaming and was an attempt to help them feel a little more accepted in an already fragmented world. F. C Stanford and the team said body positivity took the shape of a campaign to spread awareness of the harms caused by weight bias and fat shaming.

What started as a helping hand to a marginalised group has now become an excuse to not only justify being obese but also glorify it. A precise and more problematic version of the body positivity movement is fat acceptance. Unlike body positivity, fat acceptance is more convergent in its purpose of bringing the fat population together to fight the constant ridicule and prejudice they face regularly. Apart from spreading awareness, this united front against bullies has erroneously convinced people to feel proud of being obese. Marissa Dickens, with fellow scientists, examined the experiences of 44 bloggers from the Fatosphere community in their peer-reviewed article; The role of the fatosphere in fat adults’ responses to obesity stigma: a model of empowerment without a focus on weight loss.

According to researchers, to rise above the obesity stigma, these bloggers suggested reframing inappropriately directed slurs to dodge the psychological trauma that usually accompanies it and to stay clear of committing to losing weight as a consequence of the criticism. The subscribers to these bloggers reported feeling empowered and improved mental well-being as a consequence of belonging to a supportive community. As a coping mechanism, fat acceptance delusively warrants access to self-esteem but misses the target altogether, concerning itself only with self-acceptance and not the realisation of the threat obesity poses.

Harvard T.H. Chan, School of Public Health, defines obesity-associated health risks “as an illness that harms virtually every aspect of health, from shortening life and contributing to chronic conditions such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease to interfering with sexual function, breathing, mood, and social interactions”. Addressing the harmful psychological remnants of fat shaming and overlooking the urgency to lose weight is like severing the stem of a wild plant and expecting it to exterminate. A movement brought into motion only to make everyone agree with the individualised definition of obesity: fat acceptance accurately defines the cultural zeitgeist of the ongoing 2020s.

To move or become less active is a choice like restraining or giving into every urge to eat. It sure is more challenging not to fall for hunger every time, and insatiable eating habits make the struggle worse.

Fat-Free Mass & the Way Forward

Unfortunately, dodging reality won’t change the horror that is obesity. To fight this multi-faceted illness, we first need to address the relentless efforts of people wanting to impose their version of health on society to define the silver lining in this widely ridiculed disease. Then, we must stress adopting some well-needed lifestyle changes to dial the fat percentage down and enhance the fat-free mass simultaneously. R Burrows and colleagues, in their article “Low muscle mass is associated with cardiometabolic risk regardless of nutritional status in adolescents: A cross-sectional study in a Chilean birth cohort”, found that children with relatively better muscle mass were less likely to develop cardiometabolic diseases than those with low muscle mass, reporting in line with the previously observed association between fat-free mass and chronic health diseases.

In another study, “Muscle Mass Index as a Predictor of Longevity in Older Adults”, where a massive cohort of older adults was followed-up to interpret the influence of muscle mass on all-cause mortality, an inverse impact was derived. As concluded in the examples above, quality and longevity of life are both governed by muscle mass relative to the height of a person. Skeletal muscle dominates adipose tissue (body fat) in ramping up the body’s calorie expenditure at rest, aiding the total daily energy expenditure or TDEE. These benefits aren’t only available to those predisposed genetically to build muscle and are accessible to individuals capable of moving weight. To move or become less active is a choice like restraining or giving into every urge to eat. It sure is more challenging not to fall for hunger every time, and insatiable eating habits make the struggle worse.

On the contrary, satiating eating habits help dial down hunger, facilitating restraint from food when you have had enough. Journeying back from obesity can seem a little daunting at first, and adopting the conventional methods to lose fat can pose unwarranted stress on the mind and body. This usually happens when expectations hang beyond the pragmatic understanding of fat loss and meet the widely popular quick-fix methods.

The only way to deal with the carnage obesity has caused and will cause in the future, is by changing our attitude toward it. Let’s do it now before it’s too late.

Composed by: “Sarthak Kapoor is an exercise scientist associated with BASES (British Association of Sport and Exercise Sciences) certified sport and presently pursuing a master’s from Liverpool John Moore’s University in Clinical Exercise Physiology.”